In the first post of this series about crude oil load rejections, we discussed the extent of the problem, its estimated cost to producers and first purchasers, and how rejections can be predicted. These were the highlights:

- In our sample, first purchasers rejected 2.6% of crude oil loads because of high BS&W.

- The cost of rejections to an average first purchaser and producer is estimated at $1.5 million per year.

- Rising BS&W levels and falling gravity are leading indicators that a load will be rejected.

Now we will explore a practical approach to implementing workflow changes associated with rejected crude oil loads.

Under normal circumstances, there’s a standard process for collecting loads.

- Producers employ pumpers who are responsible for the crude quality from a number of leases.

- When a lease is ready to be hauled, the pumper will request that the first purchaser sends a truck to collect the load.

- The first purchaser dispatches a truck to the lease and the driver checks the crude quality (gravity and BS&W) while filling the tanker truck.

- The truck driver measures and records the gravity and BS&W. If the BS&W is within the acceptable range (generally less than 1 to 2%), they will haul the load and deliver it to a pipeline injection station. The producer will be sent a run ticket showing the volume hauled, quality, and where it was delivered to.

- If the BS&W is above the acceptable range, the driver will pump the crude back into the lease battery and send a rejection notice to the producer electronically or by leaving a notice at the lease.

- It is the responsibility of the pumper to clean or dispose of the oil before requesting another collection at that lease.

Why does this process break down when a lease enters a rejection period?

Through our analysis, we discovered that crude oil load rejects often occur in clusters. Once the rejected crude is cleaned or disposed of, the lease tends to continue producing high BS&W crude oil and is rejected for a period of time. The process that capSpire has developed is specifically aimed at reducing successive rejections. We applied a modest change to hauling procedures and analyzed this data to arrive at a solution that reduces successive crude oil load rejects by 40% in the sample data set.

What does the new process look like?

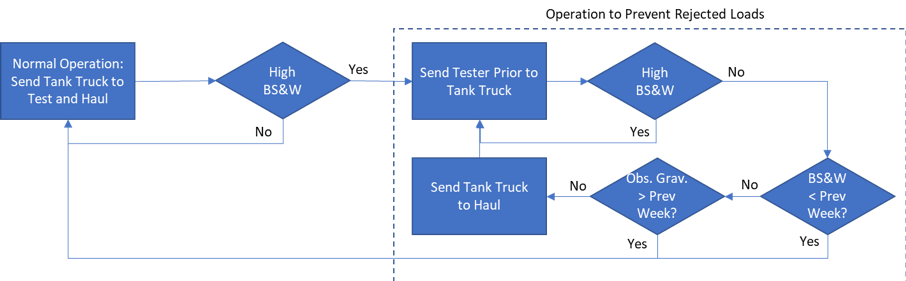

The change in process happens between steps 5 and 6 above. Once a crude oil load is rejected, that lease is flagged by the first purchaser. The next time the producer requests a load to be collected, the first purchaser sends a third-party tester to measure crude quality and record readings. Then the decision flow diagram below takes effect.

Process 5-6:

- If BS&W is high, the producer is notified that the load won’t be collected.

- If BS&W is not high, the first purchaser will send a truck to haul the load. However, the lease will remain flagged for the tester process unless two factors are present: 1. BS&W is less than the previous reading. 2. Observed gravity is greater than the previous reading.

- After the flag is removed, the lease returns to normal operations.

What are the benefits of the new process?

The new process benefits the producer and first purchaser by reducing successive crude oil rejects by 40%. As a result, the costs associated with these rejects are not incurred. Tanker truck efficiency is enhanced, producers reduce reject fees, and the added emphasis on crude quality should improve overall pumper performance.

The application of this procedure to the sample data set resulted in a simulated reduction of more than 40% in loads that were previously rejected and would have otherwise been rejected continually. Based on our estimated cost of rejects of $3 million per year, the producer and operator would save $1.2 million per year in the tested scenario.

How much will the new process cost?

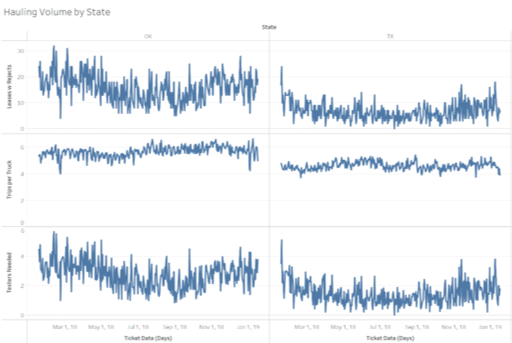

For our sample data set, we estimated that three testers would be required in addition to the crude truck fleet. The estimated all-in cost for these new testers is $600,000 per year.This image, which shows how tester truck requirements change in response to the frequency of crude oil rejects, is based on a medium-sized first purchaser. When extrapolated out to the entire industry, the cost benefits would be in the tens of millions for first purchasers and producers, and more employment opportunities in oilfield services would be created.

Ideally, the producer and first purchaser would agree to engage a third-party contractor and share the cost of the services between them. Regardless of who pays for the process, the combined effect will be a net improvement of $600,000 lower direct costs per year. More visibility and emphasis on the issue will also drive continuous improvement and have more intangible benefits on the participating companies. For more information, please contact info@capspire.com.

About capSpire

capSpire provides the unique combination of industry knowledge and business expertise required to deliver impactful business solutions. Trusted by some of the world’s leading companies, capSpire’s team of industry experts and senior advisors empowers its clients with the business strategies and solutions required to effectively streamline business processes and attain maximum value from their supporting IT infrastructure. For more information, please visit www.capspire.com.